Standing on Her Own Two Feet

Frume Halpern as Artist, Feminist, Healer . . . and Bohemian

When I started to think about the Yiddish writer Frume Halpern, author of Gebentshte hent: dertseylungen—a stunning depiction of the inner lives of those living at the American margins and a book I recently translated—as a subject for this blog, I had to reconsider the word “bohemian.” Did I really know what it meant?

In my mind, the word conjured an inherent, indeed vibrant, sociality: Greenwich Village in the early twentieth century. Mabel Dodge. The Bloomsbury circle in London. The Dada group in Paris. The Beat gatherings at Gallery Six in San Francisco. Or from an earlier time, the salon of Rahel Levin Varnhagen in nineteenth-century Berlin. Conversation on matters literary or philosophical that sparkled perhaps during an afternoon lubricated by coffee or tea and Linzer tortes or lebkuchen, or perhaps long into the night, lubricated by edgier elements: booze, smoke, or salacious gossip. A milieu of glamour, even if cobbled together on a shoestring, that might include, or be characterized by, the latest style in art or clothing or clothing as art, possibly setting the latest fashion, soon to be replicated elsewhere. And perhaps erotic freedom, a less restricted set of sexual mores.

Given these images conjured by rummaging rapidly through time, I wondered if Halpern could really be considered a bohemian. I haven’t as yet found any evidence of her participating in such salons or promoting an alternative sartorial style of any kind. But when I looked up “bohemian” in an online dictionary, I found the following definition: “a socially unconventional person, especially one who is involved in the arts.” Instead of limiting possibilities, this brief definition opened them.

There can be no question that Halpern was both socially unconventional and involved in the arts. By interviewing her family members, I learned that she separated (divorced?) from her husband, Isaack. Such a separation could not have been easy, given the social mores of the day. Halpern’s granddaughter-in-law, Judith Linn, recalls that when she was teaching preschool, she dropped by to see Halpern. They talked about Judith’s students and day-to-day matters. Frume was pleased that Judith, as a young married woman, was working and earning money. Judith informed me that family lore had it that Frume had studied to be a nurse in the old country. Because Halpern couldn’t practice nursing in the United States due to the language barrier and/or professional requirements, she became a massage therapist. She worked in the Bronx Hospital (and possibly elsewhere). She would leave the apartment at 7:30 a.m. and take the bus down the Grand Concourse. She took two buses to reach the hospital. Halpern moved into the Amalgamated Housing in the Bronx in 1942 or 1943; she had lived elsewhere in the Bronx prior to that. She lived quite close to her daughter, Nora, and for the first three years of their marriage to Judith and Nora’s son and Judith’s husband, Victor. This afforded her the economic independence so central to women’s emancipation. Living without a man and earning her own living would arguably have placed Halpern outside the mainstream of pre–second wave feminism American Jewish life.

Halpern’s life as a writer was anchored in the milieu of the communist-affiliated newspaper Morgn-frayhayt, itself an unconventional space. Her stories appeared and were written about in that publication and its associated Zamlungen. She was an active member of the Yiddish writer’s union of the IKUF, the communist-affiliated publishing house that published Blessed Hands. Leftist writers such as Itshe Goldberg, Ber Green (Ber Grin), and Isaac Elchanan Ronch (Yitskhok Elkhonen Rontsh) promoted her writing. Ronch wrote the foreword to Blessed Hands and was the chairperson of the committee that worked to get it published. Green wrote a powerful tribute to Halpern on the yortsayt of her death. In his review of a recently published anthology, Amerike in Yidishn vort (America in Yiddish Letters, compiled by Nakhmen Mayzel), Goldberg asked: “How can it be that

writers such as Sh. Dayksl, M. Bornshteyn, D. Keshir, Borekh Miler, Frume Halpern and a number of other writers are missing from this anthology? The tone and theme of the entire anthology would naturally have been enriched if Yiddish word-artists who, with their entire essence, rooted themselves in the progressive Yiddish culture of America had not been omitted or overlooked?” These writers whose lack of inclusion in an important anthology Goldberg lamented remain little (or lesser) known to today’s English (and possibly Yiddish) readers. The importance of political newspapers as an intellectual home and the nurturing center of community for Halpern, and for many Yiddish writers, cannot be underestimated.

Additionally, Halpern was a member of a literary fraternal club in the Bronx. Many decades before the possibility of online gatherings, the physical space of such a club was surely critical to Halpern’s sense of literary self. A Morgn-frayhayt article written by Y. Fisherman published some fifteen years after her death (and translated by Nora Linn and Immanuel Klein) sheds important light on Halpern’s life in the club. According to Fisherman, the members “felt very proud that this beloved and talented writer was one of them and shared their philosophy and dreams.” When the club wanted to dedicate an evening to her writing, she objected vigorously. But she did not prevail, and the evening took place. Fisherman noted that Halpern was “a gentle soul, generous, sensitive, and shy.” Fisherman also spoke at a book party for Blessed Hands and at a memorial meeting in honor of Frume Halpern on the evening of Thursday, March 3, 1966, at the IKUF Center, 189 Second Avenue, New York. Borekh Miler and Bella Goldworth are among other names that appear in accounts of events connected to Halpern. Borekh Miler was the secretary and Goldworth and Lili Miler were the finance committee members of the book committee that worked to bring these stories out of the realm of yellowed newspapers and into the book form of Gebentshte hent. Goldworth herself was a fiction writer; her novel The Unknown Relative (1976) was translated into English by Max Rosenfeld. In seeing the recurrence of these and other names, one wonders about the delicate threads of these relationships. Did these writers see each other at political events and literary readings? Did they visit each other? Attend each other’s family life-cycle events?

The defiance of social convention is apparent in Halpern’s writing as well. The very first sentence of Blessed Hands (the title story and the book) conveys the centrality that Halpern attached to women’s financial independence. Halpern writes: “Ever since Soreh stood up on her own two feet and became an independent person, her hands had been in constant contact with human bodies.” This theme returns in another story in the collection, “Goodbye, Honey,” but to considerably more ambiguous effect. Here, Molly’s ongoing struggle to keep her beauty salon going leaves her utterly depleted. She travels to Florida to rejuvenate herself and, once there, meets an older gentleman who takes an immediate interest in her. Their life together takes some unsettling turns, and the story can arguably be read as a cautionary tale on what happens when women lose or relinquish their independence. In the story “Munye the Shoemaker and Baruch Spinoza,” Munye’s wife Dvoyreh had so wanted a daughter but instead had five boys and, yes, one girl. Only she was really a half boy. The girl didn’t want to wear skirts but rather tsitses, the ritual tassels worn by males. This theme of gender dysphoria is not fully explored, but it remains a tantalizingly suggestive—indeed neon—clue for readers of Halpern’s day (and today’s readers). And there’s more. Throughout the book, there are mentions of female and male individuals whose bodies don’t quite accord with gender expectations. The aforementioned Soreh’s hands “weren’t feminine enough.” Mr. Sonn, the Hebrew teacher in “In the Convalescent Home,” holds “his small, feminine hands on his knee” when a racket interrupts his post–rest hour reverie. In the summertime, Manye the newspaper seller’s “massive, unfeminine frame was visible” (“Gray Lives”). One wonders what Halpern might have made of gender expectations and identities had she written her book at a later time. Might she have chosen to center matters of gender? Instead, reading this book with a queer lens can provide us with a sense, a glimpse, of how queerness might have been experienced or imagined by a Yiddish writer in the middle of the last century. Into that small opening we the readers can bring our own imagination and creativity.

And yet, for all the arguments that I have brought to bear here, to make my case for Frume Halpern as a Bronx Bohemian there appears to have been an austerity about her that resists any easy designation of “bohemian.” Judith Linn recalls that Halpern was not at all “frivolous or playful. All business, very serious. She carried the world’s troubles on her shoulders. She was a very formal woman.” Her grandson Robert Linn recalls: “She didn’t talk about herself at all. She was very quiet. She cared for us in her own way but she was not terribly outgoing . . . I always thought she was a sad person, but I never knew why.” The joie de vivre and the playfulness so often at work in bohemia appears not to have been readily visible to the family members who knew Halpern.

And, of course, that seriousness, that intensity, is evident in her writing, in the lives of the protagonists who inhabit her powerful stories: Two blind people who fall in love. A man in the process of losing his hearing. A mother whose young son is lynched. Members of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s family—their young sons and an aunt—who wait for them to meet their terrible fate. A “plain” young woman who is befriended by a colleague and comes into political awakening.

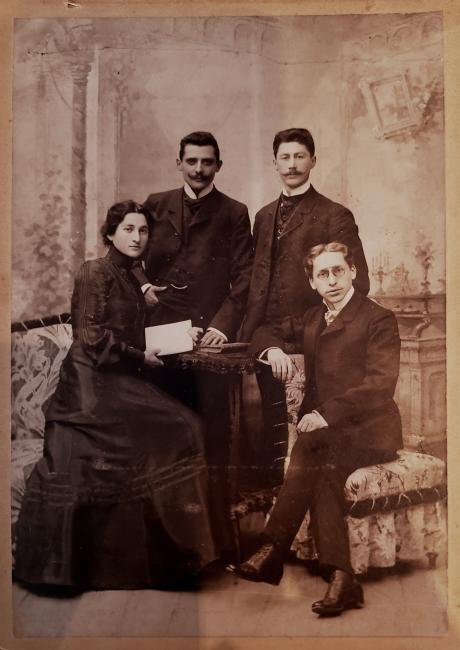

Of the Yiddish translation projects that I’ve worked on so far, Halpern has left behind the least amount of documentation. I haven’t seen any of her correspondence (received or sent) or, aside from a brief note at the end of Blessed Hands, anything nonfiction. I don’t even know exactly where she was born. Bialystok? A shtetl near Bialystok? There are several possibilities in the evidence. And even the photographic evidence that we do have raises so many questions. For example, a photo of Frume and Isaack in Bialystok, presumably shortly before their emigration, shows them both elegantly clad and unsmiling. They are standing very close to each other, with Isaack angling in front of Frume. Isaack’s arms are folded, and only one of Frume’s hands are visible. Frume is wearing a white blouse, and her hair is combed high. In another photo, Frume and Isaack are seated while two unidentified gentlemen are standing behind them. Here Frume is dressed all in dark, and the sweep of her skirts occupies much of the frame. We can practically hear the taffeta (silk?) crackling and rustling. Her hair is not upswept. In both photographs Frume’s gaze is direct and, yes, serious and intense. Far from being a wallflower, she commands the attention of the viewer. The figures are well dressed, which presumably would not have been unusual for a studio photograph. Was this their only finery? Were there others? And who were those other gentlemen? Family members? Comrades? Friends? When exactly did folks start to smile in formal photos?

In a photo taken much later in Halpern’s life, the overall mood is quite different. If she’s not actually smiling, there seems to be a twinkle in her eye, and her spirits seem up. She’s wearing some sort of pillbox hat, and there’s netting over her forehead and then tied behind. She’s wearing earrings and pearls and apparently makeup. The entire photo is bathed in a rosy, or rather peachy, glow. She’s surrounded by people; we can see one woman leaning intently forward in front of her. Across are more people leaning over a railing. What public event is this?

While I have learned a great deal during the course of my research and feel profoundly grateful to Judith Linn, Victor Linn, and Robert Linn for their support and for sharing so much with me, there is still a great deal I don’t know about Halpern. The information that is available thus becomes especially precious. But equally important is the space we give ourselves to speculate and wonder and the freedom to be at peace with the questions to which we (at least for now) have no answers.

And most crucially we have Blessed Hands. The stories in Halpern’s only book cut through the noise and the flash and the siren call of today’s devices with great emotional power, wisdom, and tenderness. These stories demand that we stop and see and listen and feel. Indeed, these stories made me feel that the author was speaking directly to me, sometimes causing me to gasp in startled recognition.

We have something else, too: a clear portrait of a figure devoted to living her life and creating her art on her own terms. A massage therapist committed to being a force for healing. A Yiddish typewriter in a Bronx apartment living room that according to Judith Linn was never put away. And a writer anchored in her Bronx progressive Yiddish literary community. In short, we have the life and work of a true Bronx bohemian.

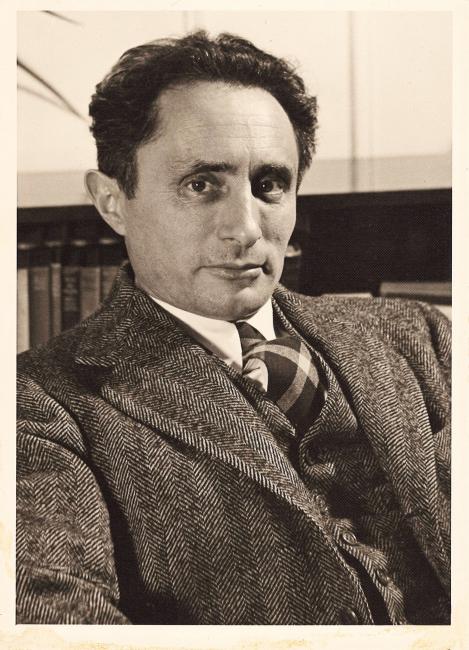

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is a poet, writer, and translator of Yiddish literature. He is the author of two books of fiction and six volumes of poetry, including A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems (2017). Prior to Blessed Hands: Stories, Taub translated Dineh: An Autobiographical Novel (2022) by Ida Maze. More details at his website.

Yermiyahu's translation of Blessed Hands: Stories by Frume Halpern was recently by published by Frayed Edge Press (Philadelphia, PA).