Motl the Cantor's Son: Reading Resources

The Book

Background and Publication

Sholem Aleichem’s career focused on the changes and challenges facing Yiddish-speaking Jews at the turn of the twentieth century: political radicalism, anti-Semitism, “romantic” approaches to love and marriage, secularization, and modernizing economies. In Motl the Cantor’s Son (Motl peysi dem khazns), this exploration draws to a close by turning to one of the central experiences of modern Jewish history: immigration from Eastern Europe to the United States.

As with all of Sholem Aleichem’s works, the composition and publication history of Motl differed greatly from what we expect of contemporary novels. Instead of a focused, unified writing process and single publication event, the work was written over approximately a decade (1907–1916) and published serially, as each chapter was completed.

Work on Motl took place largely in two bursts. The first, “European,” portion of the novel, which tells the story of Motl’s life in Kasrilevke and his family’s circuitous migration across central Europe, was written after the author’s return to Europe from a largely disappointing stay in New York City (1906–1907). Although these chapters were written in Geneva, they appeared in the New York Yiddish newspaper, Der amerikaner (The American) over the course of 1907–1908. In 1911, they were published as a book.

The second, “American,” half of Motl emerged in 1915–1916 after its author’s return to New York. Surprisingly, this new work did not begin with prose. Instead, Sholem Aleichem worked for several months to adapt the earlier chapters into an English-language film. Although it was never finished or produced, notes remain that show the author extending the narrative to include Motl’s arrival, with his family, at Ellis Island.

The final chapters of Motl were serialized both in Yiddish (in the New York-based Di varhayt) and in an illustrated English-language translation in 1916. The latter, published in the New York World and syndicated across the Pulitzer family’s twenty newspapers, reached an estimated five million readers each week and helped bring Sholem Aleichem the financial success and security that had previously eluded him even as he achieved literary celebrity. In these chapters, the author turns his eye toward life on New York’s Lower East Side, at once aware of the difficulties of immigrant life and delighting, through Motl’s optimistic eyes, in its possibilities. But at this point, Sholem Aleichem’s health was flagging and, as many critics have noted, the final chapters lack the energy and depth that characterize the beginning of the novel.

Sholem Aleichem never finished Motl. When he died on May 13, 1916, the partially-written manuscript of what is now its final chapter lay open on his desk.

Themes

Family Life

Motl the Cantor’s Son is more than the story of its narrator and title character. In many ways, his family serves as a collective protagonist, especially after their departure from Kasrilevke. At first, this is the story of his immediate family’s breakup: Motl’s father, Peysi the Cantor, dies in the book’s opening chapters and, shortly thereafter, his brother Elyahu gets married and leaves the household. Even Motl himself is briefly outsourced, working as a servant to an old and deranged scholar. But the bankruptcy of Elyahu’s father-in-law, a baker, brings the family together again under Elyahu’s entrepreneurial guidance. Elyahu’s ambitions are unsuited to Kasrilevke, where every business scheme ends in failure, but lead the family to modest success in New York. In addition to Motl, Elyahu, his wife Bruche, and Motl and Elyahu’s mother, the family unit also comes to include Elyahu’s friend Pinni and his wife Teibl. Pinni, like Motl, is a creative type—an idealistic poet whose dreams of America lead him to wild swings of emotion.

Although Motl is, as he proclaims with comic enthusiasm, an orphan, he is not isolated. The death of his father, a religious figure, carries symbolic weight (the passing of traditional Jewish life; change when confronted with modernity), yet the family unit survives this blow—not only intact, but reimagined. Together, they confront the journey to and life in the United States.

Immigration

In Motl, Sholem Aleichem describes how Jewish immigration to the United States could be circuitous and difficult even before the overseas journey began. The family’s overland encounters with border agents and bureaucracies (both governmental and Jewish) are perhaps even more bewildering than the life they encounter on the Lower East Side. As pogroms spread behind them, they find themselves among a growing mass of Jewish migrants who overwhelm aid agencies and are plagued by poverty, crime, and illness. Motl’s mother’s near-constant weeping in these scenes—which her family fears will result in her being diagnosed with the eye disease trachoma at Ellis Island—comes to symbolize the great fear of being turned away from America for health reasons.

As the family crosses into and through the Austro-Hungarian Empire, journeying from Kasrilevke to Brody to Lemberg to Krakow to Vienna to Antwerp and then London, they mirror the route taken by Sholem Aleichem and his family on their first trip to America in 1905. They, too, had to find extra-legal ways to cross the Russian border, endured the loss of personal effects, and negotiated (not always successfully) with administrators, aid workers, and immigration officials to get their papers in order.

Before entering the United States, the family endures a long wait on Ellis Island, the immigration processing center open from 1892 to 1954. From 1905 to 1915, approximately 5,000 immigrants arrived each day, making it a central and shared experience of Jewish immigration. While most only spent several hours on Ellis Island and approximately two percent were refused entry, the fear of delays and deportation was widespread. For Motl and his family, Ellis Island is the first sign that their dreams of life in New York might not match the reality.

Language

When they emigrate, Motl and his family leave one multilingual world for another, and their acquisition of and reactions to English play important roles in the story. We can think of translation—which literally means “to bring across”—as a metaphor for the larger Jewish immigrant experience. For Motl’s mother and Teibl, the encounter between Yiddish and English is traumatic, ultimately symbolizing the cultural loss that can come with immigration. They long to use familiar Yiddish words for familiar daily items like a fork. For Motl (and perhaps the author), this encounter is energizing. Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish text does not take the disdainful attitude some Yiddish literati held toward the Americanization of Yiddish but uses Motl’s natural acquisition of English as a source of linguistic play—and social commentary. As Motl learns the words he needs to navigate economic life in his new country, Sholem Aleichem introduces English words, spelled phonetically with Yiddish letters, into his original text: words like biznis, dzhab, kahstemahz, and fektri (for business, job, customers, and factory). How and to what extent to represent this effect in the English translation is a question each translator has had to answer: should they be rendered in standard English (Motl, after all, understands them easily) or spelled phonetically in a “Yiddish accent” to retain the original strangeness Sholem Aleichem put on the page?

Religious Symbolism

Motl is replete with imagery and symbolism grounded in Jewish religion. As a child who has not yet reached the age of bar mitzvah, Motl does not and cannot refer to and hold forth on biblical references and rabbinic commentators (as Tevye the Dairyman does to comic effect in Sholem Aleichem’s other stories). Instead, religious elements enter the work in other ways.

The first and second parts of Motl each begin at a key moment on the Jewish calendar: At the beginning of part one, Motl’s father dies on the holiday of Shavuos, a spring harvest festival that also commemorates the giving of the Torah and the covenant at Mount Sinai. At the beginning of part two, the most momentous episode of their sea crossing takes place on Yom Kippur, the day of fasting, judgment, and atonement often described as the most sacred day of the Jewish year.

Other religious allusions also help shape the novel. When Motl’s mother cries, for instance, she recalls the prophet Jeremiah’s image of Rachel weeping for the Jewish people as they go into exile. And Menye the calf, Motl’s companion in the first chapter, references both the sacrifices of Temple-era Judaism (recalled daily in traditional Jewish liturgy) and the well-known Passover song “Chad Gadya” (“One Kid”).

The Author

Even above Tevye the Dairyman and Motl the Cantor’s Son, the greatest character Sholem Aleichem invented may have been himself. By the time of his death in May 1916, the fifty-six-year-old author had become one of the, if not the, most widely read and respected figures in Yiddish literature. In New York, Kiev, Warsaw, and across the Yiddish-speaking world, his essays, stories, novels, and plays could be found in newspapers, on bookshelves, or on stage. And not just in Yiddish. Hailed in America as “the Jewish Mark Twain,” his sharp yet humanizing humor was already widely translated into English and Russian. In addition to Twain, his readers included the great Russian novelists Maxim Gorky and Leo Tolstoy.

But lingering too long on his celebrity would be misleading. Sholem Aleichem may have achieved a lot, but he was loved by his readers because he presented himself as one of them. In death as in life, he relished being among the common people. Although memorial events lasted a month and ranged from New York’s synagogues to Carnegie Hall, from a 200,000-person procession through the streets of the Lower East Side to a eulogy on the floor of Congress, his will announced that, “Wherever I die I want to be placed not among aristocrats, or among the powerful, but among plain Jewish laborers, among the very people itself.”

Sholem Aleichem was born Sholem Rabinovitch in the mid-size town of Pereyaslav and raised in the small village of Voronkov, near Kiev, then part of the Russian Empire. His father, Menachem, was a pious Jew who loved the new, emerging Hebrew literature of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment). His son thus received both a traditional (Jewish) and a modern (secular) education.

But just as forces beyond their control buffet Sholem Aleichem’s characters, so too with Sholem Aleichem himself. When he was an adolescent, his father, a successful merchant, was wiped out by a dishonest business partner. And in 1872, a cholera outbreak claimed the life of Sholem Aleichem’s mother, Khaye-Esther. Like his most famous characters—Tevye the Dairyman, Menachem-Mendl, and Motl—Sholem Aleichem’s life was continually marked by tides of history, love’s whims, and dramatic reversals of health and fortune. As the child grew into the writer, he carried awareness of such abrupt, unpredictable changes with him.

In 1883, he married Olga Loyev, the daughter of a wealthy Kiev landowner whom he had been hired to tutor. Their marriage would last until his death and produce six children. In that same year, 1883, Sholem Rabinovitch published a story in the Folksblat (the People’s Paper) under the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem for the first time. The name is a Yiddish greeting: literally, “Peace be upon you,” but more accurately translated as, “Hey—How are you?” From his emergence in the Folksblat, Sholem Aleichem would grow into more than just a pen name. He was also a persona, a narrator, and, in many cases, a character in the very stories he told: the friendly, familiar, chatty figure, like a cousin or a friend-of-a-friend from out of town who you implicitly trust with your most important stories (even though you can’t quite remember his name). Sholem Aleichem’s most famous character, Tevye, delights in his encounters with Sholem Aleichem (the character) and addresses his monologues to him. Over time, as his popularity grew, Sholem Aleichem became intertwined with Sholem Rabinovitch, blurring the lines between fact and fiction.

By 1890, Sholem Aleichem was an established and successful figure in the world of Yiddish literature, with a half-dozen novels and plays to his name. He had come into a small fortune after the death of his father-in-law, who left him as the executor of his estate, but Sholem Aleichem was no luckier in business dealings than his own father or his characters: he lost the entire inheritance on the stock market. In the decade that followed, Sholem Aleichem created his most enduring characters. The ambitious ne’er-do-well Menachem-Mendl and his practical, level-headed wife Sheyne-Sheyndl debuted in 1892, and Tevye the Dairyman in 1894. Though today we often think of Sholem Aleichem’s works as “novels,” they were first published, serially, as linked stories written over a decade or more. This writing process is partly responsible for the writer’s ability to track his major theme—the encounter between traditional Eastern European Jews and the modern world—so effectively. Just as history is not planned and plotted from the start, neither were the lives of Tevye, Menachem-Mendl, or, later, Motl. Instead, their author observed and created as the world around him changed, so that his stories incorporated the rise of socialism and Zionism, continued Jewish emigration from the Russian Empire, the changing modern economy, the growth of rail travel, and his own roller-coaster fortunes, among other phenomena.

Both sympathetic and ironic, Sholem Aleichem became the great chronicler of the encounter between traditional Jews and the rapidly modernizing world in which communities were increasingly interconnected, and the barriers of language, geography, nationality, and even religion were more permeable than ever. Traditional customs were challenged and did not always survive intact. Communities were no longer bound to a single place as Jews began traveling by rail across western Russia for business or pleasure and also continued immigrating to America.

By the 1910s, Sholem Aleichem himself had become a wanderer. Tsar Nicholas II’s 1905 liberalizing constitutional reforms had been followed in swift fashion by pogroms in Odessa, Kiev, and throughout the Pale of Settlement (the region in which most of Russia’s Jews lived). In the face of this violence, Sholem Aleichem and his family, like so many other Jews, left Russia for New York. Their convoluted journey, including illegal border crossings, medical anxiety, delayed paperwork, and detours through London, Paris, and Switzerland, informs Motl’s European wanderings.

Sholem Aleichem’s New York stay was brief and disappointing. Newspapers folded, plays flopped, and promised paychecks appeared only after great persistence on the author’s part. Though he delighted in the small innovations of American urban life, by 1907 he was back in Europe, a diagnosis of tuberculosis requiring him to spend much of his time in warm-weather resorts near the Mediterranean.

An impending World War forced Sholem Aleichem’s final migration, back to New York City, in 1914. By this time he had published the first volume of Motl the Cantor’s Son, toyed seriously with transforming it into a silent film, and begun sketching a sequel. In writing this sequel, Sholem Aleichem took up a new theme, perhaps the only aspect of the changing modern Jewish world he had not yet described in detail: life in the United States. Thus, in the final years of his life, though he was increasingly ill, deeply aware of his own mortality, and still grieving the 1915 death of his eldest son, Sholem Aleichem chose to explore the new world around him and to experience it—on the page, at least—through the eyes of a mischievous and amazed child.

Multimedia Resources

- There are eight different version of Motl peysi dem khazns (Motl the Cantor's Son) digitized and available in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.

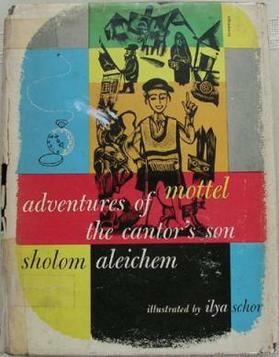

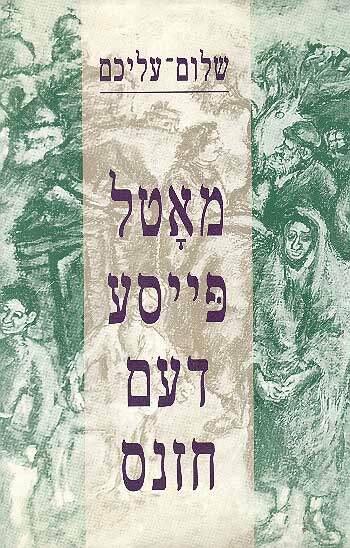

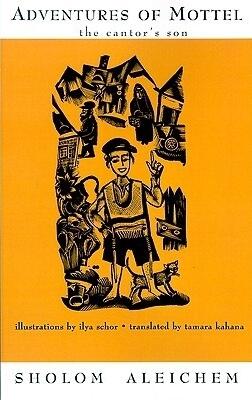

- These images of book covers from Yiddish and English editions of Motl peysi dem khazns (Motl the Cantor’s Son) demonstrate how the marketing of the book has changed over time. (See also images 9, 10, and 13 from the slideshow “Sholem Aleichem’s Works” on the Yiddish Book Center’s Sholem Aleichem finding aid page.)

Book Covers Through the Years

-

You can listen to an audio recording of Motl peysi dem khazns (Motl the Cantor’s Son) in the original Yiddish.

-

Sholem Aleichem passed away before finishing Motl the Cantor's Son. "We Moofe" is the opening of a new chapter in Motl's adventures, and it ends with an explanatory note by Sholem Aleichem's son-in-law and literary executor, Y.D. Berkovitz. A portion of this translation by Larry Rosenwald originally appeared in Pakn Treger (Summer 2016).

-

In this Wexler Oral History Project excerpt, Bel Kaufman, z"l, granddaughter of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem and author of award-winning novels, describes her favorite of her grandfather's characters, Motl the Cantor's Son, and the experience of sharing in his adventures.

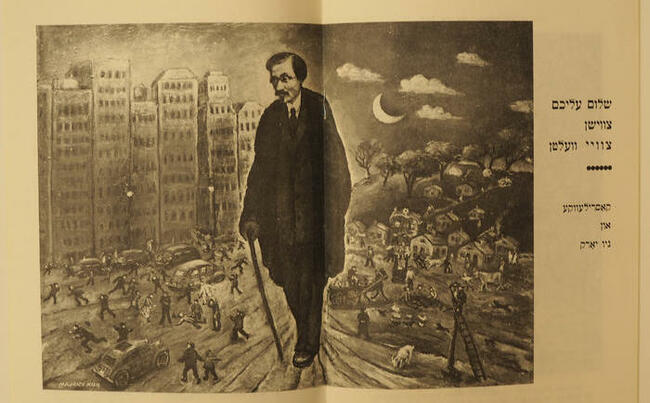

- This illustration, “Sholem Aleichem Between Two Worlds: Kasrilevke and New York,” is a reproduction of a painting by Moyshe (Maurice) Kish (1895–1987) in a 1972 Yiddish-language booklet exploring Jewish folk motifs in Kish’s work. Kish, a near-contemporary of the fictional Motl, was born in Latvia and immigrated to New York in 1912, where be became a painter, Yiddish-language poet, and labor activist. He had a reputation, akin to Sholem Aleichem’s, for depicting issues important to the average person.

- The documentary Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in Darkness (2011), directed by Joseph Dorman, explores the author’s life and works. The trailer, in addition to providing an introduction to Sholem Aleichem, includes visual depictions of Jewish life at the turn of the twentieth century.

- The 1921 Yiddish song “Di grine kuzine” (“The Greenhorn Cousin”) tells the story of an immigrant to New York as she develops from a naïve “greenhorn” to a jaded cynic. It makes for a useful comparison with the attitudes and experiences of Motl, Pinni, and other characters.

- SholemAleichem.org contains information on the author’s life and works as well as multimedia archives and other resources.

Questions for Discussion

Symbolism and General Questions

- The first two chapters of Motl are heavily symbolic. In the springtime, Motl befriends his neighbor’s calf, Menye, while his father is ill. Just before the holiday of Shavuot, the neighbors sell Menye to the butcher and his father dies on the holiday’s first day. What concepts would you associate with a calf, a father/cantor, springtime, and Shavuot? How (if at all) do these concepts appear in the novel? Try to define and describe the symbolism Sholem Aleichem uses in these early chapters.

- Even before Jews began immigrating in large numbers to the United States, the journey across the Atlantic was often compared in the American literary imagination to the Jewish Exodus from Egypt. Sholem Aleichem uses this metaphor when describing Motl’s journey on the Prince Albert in a chapter called “Crossing the Red Sea.” But he adds another layer by using this chapter to tell the story of a storm that strikes on Yom Kippur. What are your expectations of an immigration story called “Crossing the Red Sea”? Why might Yom Kippur be associated with a storm? What effect does this symbolism have on their voyage?

- Sholem Aleichem’s writing has often been described as provoking “laughter through tears.” Do you believe this assessment applies to Motl? How would you describe the sense of humor displayed by Motl (the character)? What about his brother’s friend Pinni? The book’s author?

- Sholem Aleichem was considered a master of the feuilleton, a genre of short, serialized, and entertaining essays, sketches, stories, or novels that was central to popular Yiddish literary culture. In what ways does this episodic format shape Motl?

- Each of the major characters has an action/activity that attaches to them: Motl sings and draws, Elyahu starts businesses, their mother cries, and Pinni writes. What does each action reveal about the character? How do you feel about the fact that while male characters are given creative activities, the novel’s central female character only worries and cries?

- When Sholem Aleichem died, the manuscript of Motl lay incomplete on his desk. As our version closes, Motl and his family prepare to move and take ownership of a small shop. How would you have finished Motl’s story? What kind of scene or event would be its final episode? How old would Motl be? Would your ending be optimistic or pessimistic?

The Child’s Perspective

- In writing about one of the central events of modern Jewish history, immigration to the United States from Eastern Europe, Sholem Aleichem made the defining decision to speak from a child’s perspective. What effects do you think this perspective has on the storytelling? Does Motl understand the events he lives through?

- Can you think of other works—novels, short stories, poems, movies—that depict serious subjects from a child’s perspective? What are they? What qualities (humor, naiveté, innocence, wonder, confusion, horror) do they add to the story being told? How are they similar or different from the use of a child’s perspective in Motl? Why do you think the creators of these works used a child’s perspective? Why might Sholem Aleichem have done so?

- This novel tells the story of a group of immigrants who remain together throughout their journey. The events it narrates could have been told from any of their perspectives. How would the novel have changed if Motl’s mother were the narrator? His brother (Elyahu)? Elyahu’s wife, Bruche? Their friend Pinni?

- “I have it good—I am an orphan,” Motl exclaims (153). Are there (symbolic, thematic) ways that Motl’s orphaning extends beyond his father’s death? How might we connect this to themes and concepts related to immigration, such as assimilation, secularization, and the need to learn a new language? In the novel’s title, he remains “Motl the Cantor’s Son.” In what way(s) does he continue to fulfill this familial role?

An Immigration Story

- Many of you may have had friends, relatives, or ancestors who immigrated to the United States. If you were asked to tell the story of their immigration, where would you begin? Does Motl’s story match these expectations? Why might Sholem Aleichem begin the story where and when he does—in Kasrilevke, well before anyone has considered leaving?

- Immigration stories involve borders, whether these are political, geographic, linguistic, or cultural. Motl is surprised by his experience with physical borders: “The border, I thought, must be something with horns, but it turns out to be nothing of the kind: the same houses, the same Jews, the same Gentiles as ours. They even have a market with shops and stalls—everything exactly like ours" (223-224). What are geographic and political borders like for Motl and his family? What changes when they cross borders or change cities? What stays the same? What might this say about the relationship between Jews and nations at this point in time?

- As they prepare to depart for the United States, Motl, Elyahu, their mother, and Pinni all express different ideas about what life there will be like—for example, Pinni’s repeated cry of “Columbus!” How do the characters imagine America before their departure and during their journey? How are these expectations met or not fulfilled once they arrive?

- Motl’s mother’s weeping is a major motif and plot element throughout the book. As their journey progresses, Elyahu becomes increasingly convinced that crying will lead immigration officials to reject her because of her eyes. (See the chapter titled “The Gang Is Here!”) What are some of the reasons their mother cries? How do her tears relate, thematically, to the novel’s immigration story? What kind of immigrants (in Elyahu’s imagination) does America want and/or not want?

- In Kasrilevke and in New York, Motl and his family engage in a series of different business ventures and careers. But New York City is far from rural, pre-industrial Kasrilevke. How does the nature of work change over the course of the novel? Can you identify differences between Kasrilevke’s “business ventures” and New York’s “jobs”?

- After their release from Ellis Island, it’s the sound of New York that stands out to Motl: "Trrrach-tarrrerach—tach-tach-tach! Tach! Dzin-dzin-dzin-glin-glon! Hoo-hooooo! Fee-yoo! Ay-ay-ay-ay! . . . These are the sounds that greet us when we land in New York. As long as we were on water, we were calm, but the moment we are standing with both feet on American soil, we are overcome by panic" (308). What are some other ways in which the characters are shocked or overwhelmed by their encounter with New York City?

- To this day, Ellis Island continues to play an important role in the Jewish American imagination and the cultural history of American immigration. When you think of Ellis Island, what comes to mind? Do the experiences of Motl and his family match your expectations? What events or details are surprising? How does the experience of Ellis Island change the family’s perceptions of America?

—Joshua Logan Wall