The Family Moskat: Reading Resources

The reviewers spoke of the first edition of The Family Moskat as a monument to the millions of Jews in Poland who had been slaughtered and scattered over the face of the earth in the decade before. If the book is a monument, it is a monument with a difference. It does not simply extol or glorify its subject as monuments so often do. Singer’s feelings about his fellow Jews have something in common with those expressed by Mark Twain: “The Jews are human; that is the worst that anyone can say about them.”

Milton Hindus, “A Monument with a Difference,” New York Times, 1965.

Finding Aid: Isaac Bashevis Singer

Before diving into The Family Moskat, it is worth consulting the Finding Aid: Isaac Bashevis Singer resource on the Yiddish Book Center’s website. Saul Zaritt compiled Singer-related resources available on our website, including interesting and useful background information. Zaritt’s introduction to the Finding Aid, “Trickster, Chronicler, Traitor: An Impossible Portrait of Isaac Bashevis Singer,” provides a thoughtful invitation into the writer’s world.

The Family Moskat

The Family Moskat was initially published as serialized fiction in the Yiddish-language newspaper Forverts (The Jewish Daily Forward). However, after the first chapters were published, in 1945, Forverts’ editor-in-chief Abraham Cahan wanted to drop the serialization. Cahan, who was known for inserting himself into authors’ writing processes, had his own thoughts about where the story line ought to go, but Singer refused to incorporate his ideas. Though the conflict between Singer and Cahan only grew, the serialization continued, and the novel was printed in installments until the story’s completion in 1948. (While it was being published in Forverts, The Family Moskat had a second life as a radio serial on WEVD, New York’s big Yiddish radio station; a new chapter aired live every Sunday, and Singer himself wrote the scripts.)

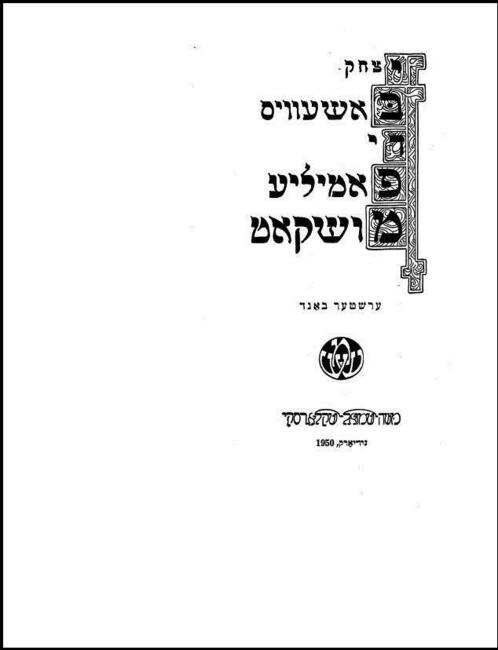

The Family Moskat was subsequently published in two volumes as Di familye Mushkat in 1950; volume I and volume II are available in our Digital Yiddish Library. A one-volume English translation, The Family Moskat, was published the same year by Alfred A. Knopf. On the title page, the named translator is A. H. Gross; however, Abba (Abraham) H. Gross died before he finished the translation. The work was completed by his daughter, Nancy Gross, with collaboration from Abba’s friends Maurice Samuel and Lyon Mearson.

Finalizing the English translation for publication was trying for other reasons as well: the editor, Herbert Weinstock, pushed for further editing and cuts to the manuscript for the English translation, suggestions Singer resisted. According to Paul Kresh’s biography Isaac Bashevis Singer: The Magician of West 86th Street, publisher Alfred Knopf himself wrote a letter to Singer arguing—quite strongly—for substantial changes to the text:

I must confess that I am greatly disturbed by Mr. Weinstock’s report of his last conversation with you following your receipt of his long letter of August 19. Four of us have now read carefully the manuscript of THE FAMILY MOSKAT and I am one of the four. I agree heartily with everyone that this book is likely to have a very poor chance indeed with the American bookseller if it is not substantially cut. I realize how painful an author finds such surgery and how easily and freely his blood flows; and sometimes I am very reluctant to press my point. But in your case there is such unanimity of opinion and I am, myself, so sure that my advisors are correct in their judgement, that I must beg of you to give weight to my judgement in a matter of this kind.

As a matter of fact, when we made our agreement with you for the book, it was my understanding that the question of cutting would be decided finally by Mr. Gross and that there would be no such appeal from his decision. I had just the arrangement with your dear brother in the case of THE BROTHERS ASHKENAZI. There Maurice Samuel was the judge. Of course one cannot guarantee results in advance of publication, but certainly your brother had no reason in the end to feel that he had made a mistake in following our advice and Samuel’s in cutting very considerably THE BROTHERS ASHKENAZI.

There is no reason at all why THE FAMILY MOSKAT should not be made from the point of view of the American reader into a very much better novel than it now is. And this without destroying the quality which you seek to preserve in it and which I respect as being a sort of monument to a life that has ceased to exist and will never exist again.

After additional back and forth between the two, Singer acquiesced and, together with the editors, cut ninety pages from the manuscript for the English translation. When the book was published, he was unhappy with the changes to which he agreed and vowed to never work with Knopf again.

Reception of The Family Moskat

One of the earliest reviews in English of The Family Moskat appeared in Commentary magazine in 1951. The review, by Solomon Bloom, was mixed; Bloom spent much of the review comparing The Family Moskat to The Brothers Ashkenazi—as did Alfred Knopf—and confessed his preference for the writing of the elder Singer, I. J. Other reviews appeared in the New York Herald Tribune, The New Yorker, the Forward, the New York Times, and The New Republic. An additional article about Singer’s writing appeared in The New York Review, written by none other than poet laureate Ted Hughes.

Later reviews approached the novel from a different perspective; Milton Hindus’s review in the New York Times in 1965 saw the novel as a tribute to a Jewish people lost in the Holocaust. The reviewer gave a largely positive review but expressed frustration that there were too many characters and that they were underdeveloped. His biggest issue, however, was with the differences between the ending in the Yiddish text and that of its English translation (note: this excerpt contains spoilers!):

This feeling of Singer’s is somewhat muted in the English version, which ends on an ominous, nihilistic note as the dispirited intellectual, Hertz Yanovar, tells the hero, Asa Heshel, in the midst of the bombardment of Warsaw: “The Messiah will come soon.” When the latter gazes at him blankly and asks, “What do you mean?” his answer is: “Death is the Messiah. That’s the real truth.”

Such an ending made a marked impression on the initial readers of the book in English, but in the Yiddish text the story is rounded out an additional 11 pages. These pages describe the escape of a pathetically small remnant of Jews toward Palestine as the bombed Moskat mansion collapses in a fiery ruin, and they permit the author to end, however tremulously, on an affirmative note. The Messiah is mentioned in the last sentence of the Yiddish text, too, but there he signifies, as he traditionally does, not death but hope and redemption. In 1950, such an ending may have been dropped because it seemed fatuously sentimental so soon after the war. Now, it is regrettable that Singer’s softer ending has not been restored in the new edition. Should another edition ever be called for, I hope that this will be done. The coda is certainly not superfluous; it contains some of the most eloquent and moving passages in the whole book.

Though he ultimately approved and made the cuts to the English translation of The Family Moskat that Knopf insisted on, Singer was unhappy with the edits. Yet in the English translations of his works that followed, Singer’s approach remained much the same: he cut and altered his novels and short stories repeatedly. He might have opted to change the ending of The Family Moskat regardless of the publisher’s wishes.

The Translation Process

Singer edited his own novels and stories, sometimes altering significant parts of the text, for translation into and publication in English. In an interview with Cyrena N. Pondrom, Singer explained: “It happens often with me, working on the translation and working on the book itself go together, because when it’s being translated I see some of the defects and I work them—so in a way the English translation is sometimes almost a second original. I cut while I translate and I add sometimes.” Singer’s translators, most of whom did not know Yiddish, would generally take down his English versions in dictation. As Singer roughly translated and edited his Yiddish into English, the translators polished Singer’s English and typed it out. Ruth Whitman discusses her experience working as Singer’s translator in her essay “Translating with Isaac Bashevis Singer” in Critical Views of Isaac Bashevis Singer, by Irving Malin.

We can also glimpse Singer’s translation process through his son Israel Zamir’s analysis in Zamir's Wexler Oral History Project interview and from filmmaker Asaf Galay's interview with The Shmooze, the Yiddish Book Center’s podcast. Galay’s documentary, The Muses of Bashevis Singer, delves into Singer’s translation process, considering and uncovering the history of his “harem” of mostly young, female translators and their vital role in his work and life.

Suggested Resources

Isaac Bashevis Singer:

- For straightforward biographical information about Singer, read the YIVO Encyclopedia article.

- For a more literary portrait, read Jonathan Rosen’s article “The Fabulist” in the New Yorker.

- For a clip of Singer’s lecture upon receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978, listen to the audio recording on the Nobel Prize site.

- For archival records, see the inventory of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s papers at The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

- For additional Yiddish Book Center resources, read the online version of the recent Pakn Treger issue focused on all things Isaac Bashevis Singer.

- For more on Singer’s conflict with Abraham Cahan, read Janet Hadda’s chapter “Bashevis at Forverts” in The Hidden Isaac Bashevis Singer, edited by Seth L. Wolitz.

- For more on Singer’s conflict with Knopf, read Paul Kresh’s biography Isaac Bashevis Singer: The Magician of West 86th Street.

Oral history interviews:

- Isaac Bashevis Singer’s son Israel Zamir’s full oral history interview is available on the Yiddish Book Center’s website, as are excerpts from the interview. Check out this clip in which Zamir discusses his father’s relationship with his elder brother, Israel Joshua Singer, and the brothers’ writing.

- Gloria Fein discusses her impressions of Singer based on various encounters with the writer, and how she came to understand and problematize his interactions with women.

- Jan Schwarz, associate professor in Yiddish at Lund University, discusses The Family Moskat and the impact of Singer's work on his life.

- Marcin Wodzinski, director of the Centre for the Culture and Languages of the Jews at the University of Wrocław, discusses the impact of Singer’s work on Polish translations of Yiddish literature.

The Family Moskat in academic writing and analysis:

- Leslie Field’s article “The Early Prophetic Writer Isaac Bashevis Singer: The Family Moskat” in Studies in American Jewish Literature, No. 1, Isaac Bashevis Singer: A Reconsideration, 1981.

- Haike Beruriah Wiegand’s article “Jewish Mysticism and Messianism in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Family Chronicle Di Familye Mushkat (The Family Moskat)” in European Judaism, Vol. 42, Issue 2, 2009.

- Susan Slotnick’s article “The Family Moskat and the Tradition of the Yiddish Family Saga” in a collection of essays edited by David Neal Miller, Recovering the Canon: Essays on Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1986.

—Sarah Quiat, 2018-19 Fellow