Blessed Hands: Reading Resource Guide

A selection of the Yiddish Book Center’s Great Jewish Books Club

We don’t know much about Frume Halpern. She was born Frume Tarloff in or near Bialostok in the 1880s, though her exact birthdate is unknown. In 1900 she married Isaack Halpern and in 1904 emigrated to the United States, followed by her husband a year later. In the United States the couple had two children, Nora and Vera, before divorcing at an unknown date. For most of her life Halpern worked as a massage therapist at The Bronx Hospital, an occupation that is reflected in her work. Many of her stories are about the sick or dying and are set in a hospital or another healthcare setting. In 1942 or 1943 she moved into the Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx. Her relatives recall her being “friendly but cool . . . sober, serious . . . not effusive, not demonstrative.” Near the end of her life she developed glaucoma and began to lose her eyesight, sending her into a deep depression. She took her own life on September 24, 1965.

We know little about her personal life and not much more about her literary career. Her cultural milieu seems to have centered around the Morgn frayhayt (Morning Freedom), a communist Yiddish newspaper where she published most of her work, along with a few other publications. Whether she was herself a member of the Communist Party, or considered herself a communist, is unknown. Some tendencies of American Communism do appear in her writing, including positive, if veiled, allusions to the Soviet Union and a concern with the lives of people foreign to her own background and experience, particularly Black Americans, whose cause had been taken up by American communists. She appears to have been well regarded by her peers, who championed her work and helped publish her only book, Gebentshte hent (Blessed Hands), which appeared in Yiddish in 1963, shortly before her death.

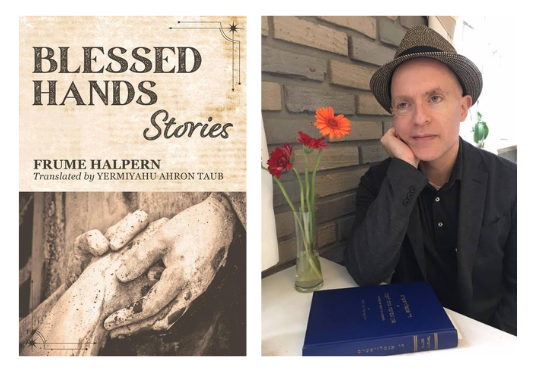

What we do have, however, is her work. Now, with Yermiyahu Ahron Taub’s translation of Blessed Hands, we have the entirety of her collected stories in English. As Taub writes in his afterword, “Halpern was a voice, indeed a literary advocate, for the marginalized—not only the poor, but those rendered ‘other’ by illness, handicap, race, not measuring up to conventional standards of beauty, and social opprobrium. Her word takes us into corners we may prefer to avoid.”

Four Questions

-

What do you make of the structure and style of Halpern’s stories? Do you find them satisfying? Do they conform to standard notions of the “short story”?

-

Most of these stories take place in midcentury America—sometimes in Jewish or Yiddish-speaking contexts and sometimes not. What kind of viewpoint do they offer on their place and time? What distinguishes them from English-language fiction from the same period?

-

Most of Halpern’s writing appeared in the communist newspaper Morgn frayhayt, although it’s unclear how she identified politically herself. Does knowing that background change your reading of the stories? Do you think her work expresses a certain type of politics?

-

Halpern did not shy away from depicting characters different from herself, including Black Americans. What was your impression of those pieces? Do you think they stand up over time?

Explore the Sections Below to Learn More about Frume Halpern and Blessed Hands: Stories

Q&A with Translator Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

Read Halpern’s Writing in Yiddish and English

Learn about Halpern’s Intellectual Milieu

Read Reviews of Blessed Hands

Q&A with Translator Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

Yiddish Book Center: How did you find out about Frume Halpern?

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub: I found her in some anthologies of translated Yiddish stories. She’s not an unknown figure. And during her own day, among the leftist press and intelligentsia, she would have been known. In fact it was a group of advocates that brought out the book.

Yiddish Book Center: What drew you to her work?

Taub: I was drawn by her deep compassion—I think of her as a literary advocate for the marginalized. She wrote a lot about the sick and people in various states of being sick, potentially related to her work in the Bronx Hospital. I think I connected with this writer on an emotional, visceral level—her lyricism, the fragility and the courage of her writing, spoke to me. There were moments when I felt that she could have been speaking directly to me as a reader.

Yiddish Book Center: In your afterword you write about the experience of translating this book during the COVID-19 pandemic. How do you think Halpern’s work speaks to our time?

Taub: I think this book is universal. Who among us has not experienced the dread of hospitals? There is specificity too—she writes about African-Americans, which would not have been unusual among communist writers. There are plenty of stories in the book about non-Jews. There’s a story where she gets into the mind of a racist and antisemitic nurse. She didn’t shy away from unseemliness; I think she looked at it head on. She definitely made a point to reach outside of herself and to bring her imagination to people outside of her identity.

Yiddish Book Center: Can you give us a sense of how she was regarded by her peers?

Taub: I think this book was well received, although the reviews were not without criticism. Maybe some felt that her stories were too dark. But there are moments of light too throughout. A number of people on the publication committee were very well known. This was a very prolific crowd.

Yiddish Book Center: Do you have a sense of the publication history of the pieces in this volume? They were all in her Yiddish collection, but are they presented chronologically? Is there another rationale behind their ordering?

Taub: She does say that they appeared in the previous two decades, so I assume that meant in the 1940s and 1950s. There may have been some that were even earlier. I didn’t track down when each story appeared. I think with all of my translation projects, I have to balance how much I can be a precise literary historian versus leaving it to future scholars to carry it forward. There are new generations of Yiddish studies scholars and there are all kinds of things they’ll discover. We all do that—we build on the generations that came before.

Yiddish Book Center: She was a leftist politically and maybe a Communist. Can you describe her politics? Other than the content of her fiction, how did she express herself politically?

Taub: Given the knee-jerk reaction people have to the word Communist, I’ve been reluctant to use it. That word just shuts people down, at least in the American context. But I think there’s so much in her writing that is worthwhile and compelling. It’s part of the complexity of this literary encounter all these decades later.

A lot of the stories don’t fit a neat Marxist proletarian framework. I think she was chiefly concerned with people at the margins, but I think what those margins were didn’t necessarily conform with the standard line. Did the leftist line talk about young women that men look right past? I do think there’s a specific Halpernian vision, a way of looking at the world.

Yiddish Book Center: There’s not a lot of biographical information about Halpern available. What sense did you get of her as a person?

Taub: I feel really, really lucky that I managed to interview three of her family members, because without them I wouldn’t have known so many things. But with Yiddish you’re racing against the clock, you’re trying to find people who knew the author. But it’s also about being OK with what you don’t know. I think in the future there may be projects where I have even less information, where it’s literally just the text or maybe a couple reviews. Do I take that on? Is it enough? Maybe we create the space for imagining a life. There are so many possibilities.

Listen to another interview with Yermiyahu Ahron Taub on the Yiddish Book Center’s podcast, The Shmooze, below.

Halpern published only one book, which has now been translated in its entirety. But you can still read the original, Gebentshte hent, in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.

Read Gebentshte hent in the original Yiddish

If you haven’t yet been able to get a copy of Blessed Hands, you can read an excerpt, the story “Rusty, My Friend,” below.

Halpern’s Intellectual Milieu

Most of Halpern’s writing was originally published in the Morgn frayhayt (Morning Freedom), a communist Yiddish newspaper. While little is known about Halpern’s own life, there is more information available about the intellectual, cultural, and political milieu surrounding the newspaper.

Some of the most important sources about the Morgn frayhayt are in Yiddish. The most comprehensive of these may be a book written by the paper’s longtime editor Peysekh (Paul) Novick, titled Jewish Life in America and the Role of the Morgn frayhayt, which you can read in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.

Read Jewish Life in America and the Role of the Morgn frayhayt

Another book about the Morgn frayhayt in Yiddish is this illustrated album dedicated to the paper’s founding editor, Moyshe Olgin.

Read this illustrated book about Moyshe Olgin

In addition to Yiddish sources, there has been a fair amount of English-language scholarship on the Yiddish left, including its Communist elements. In this recorded public program you can hear scholar Tony Michels talk about “The Yiddish Press and Racism in America, 1880–1920.”

Watch a virtual program with Tony Michels

And here you can watch a public program featuring several scholars discussing the history of Yiddish and social justice:

Watch “Yiddish and Social Justice with Alyssa Quint, Amelia Glaser and Tony Michels”

Blessed Hands has already received a number of favorable reviews. In the Broad Street Review, Helen Walsh writes: “Halpern has an eye for the human body’s influence over the fate of its owner, both as this fate is imposed by society and as it is perceived by her characters.” You can read her review here.

Read the full review in Broad Street Review

According to Kirkus Reviews, the book is “a fascinating short story collection offering glimpses into the lives of those usually unobserved.”

Read the full review in Kirkus Review

And Jamie Herndon at Foreword Reviews writes that “The stories read like interludes—short glimpses into individual lives, strung together into a whole. There are no resolutions or tidy endings for these manual laborers and people who lost countless loved ones, or for the lonely, the struggling, and the sick.”

Read the full review in Foreword Reviews

Finally, Taub’s translation has also received a review in Yiddish from the Forverts, which you can read here.